I wrote and published this in November 2013 on Tumblr, and it’s had a lot of love over the years, but Tumblr seems to be on the verge of obsolete, so it’ll live here now too. With updates!

September 2013:

I love falling down rabbit holes.

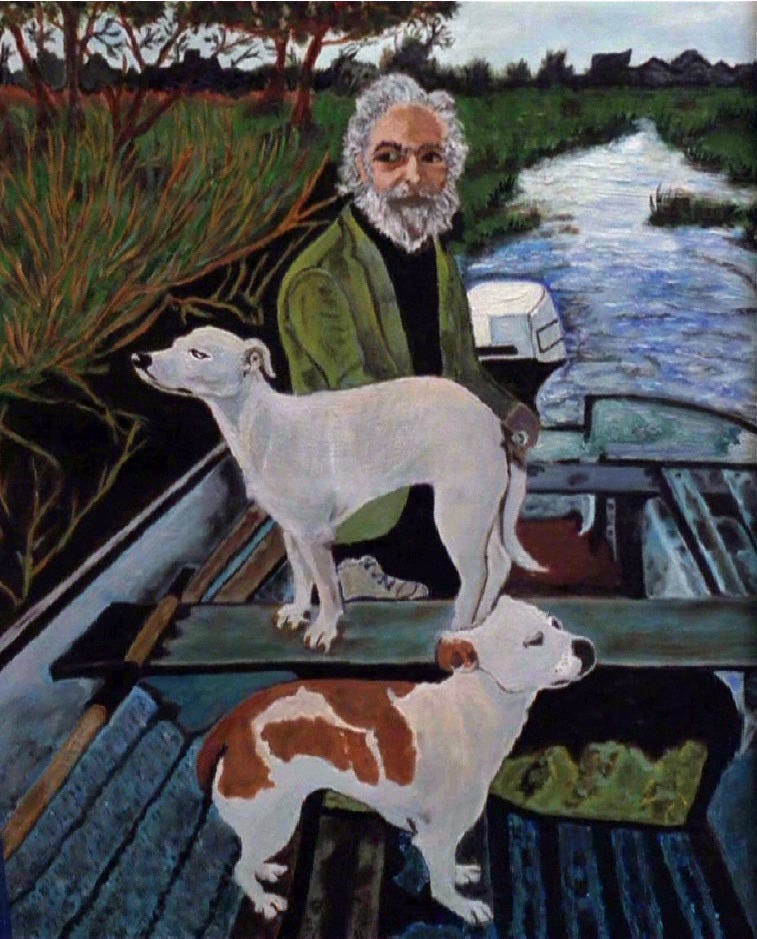

Last week, for my friend Nick’s birthday, our artist pal Shehzad made this – a replica of the painting Martin Scorsese’s mother shows off in Goodfellas. Shehzad bashed it out in five hours before dinner.

We love that scene. It’s so absurd, so morbid, so funny – so lived-in.

David Chase said The Sopranos “learned a lot” from that bit. Catherine Scorsese’s line “Did Tommy tell you about my painting?” was scripted, but much of the rest, including Joe Pesci’s “One dog goes one way and the other dog goes the other way” was improvised (watch Scorsese talking about it here).

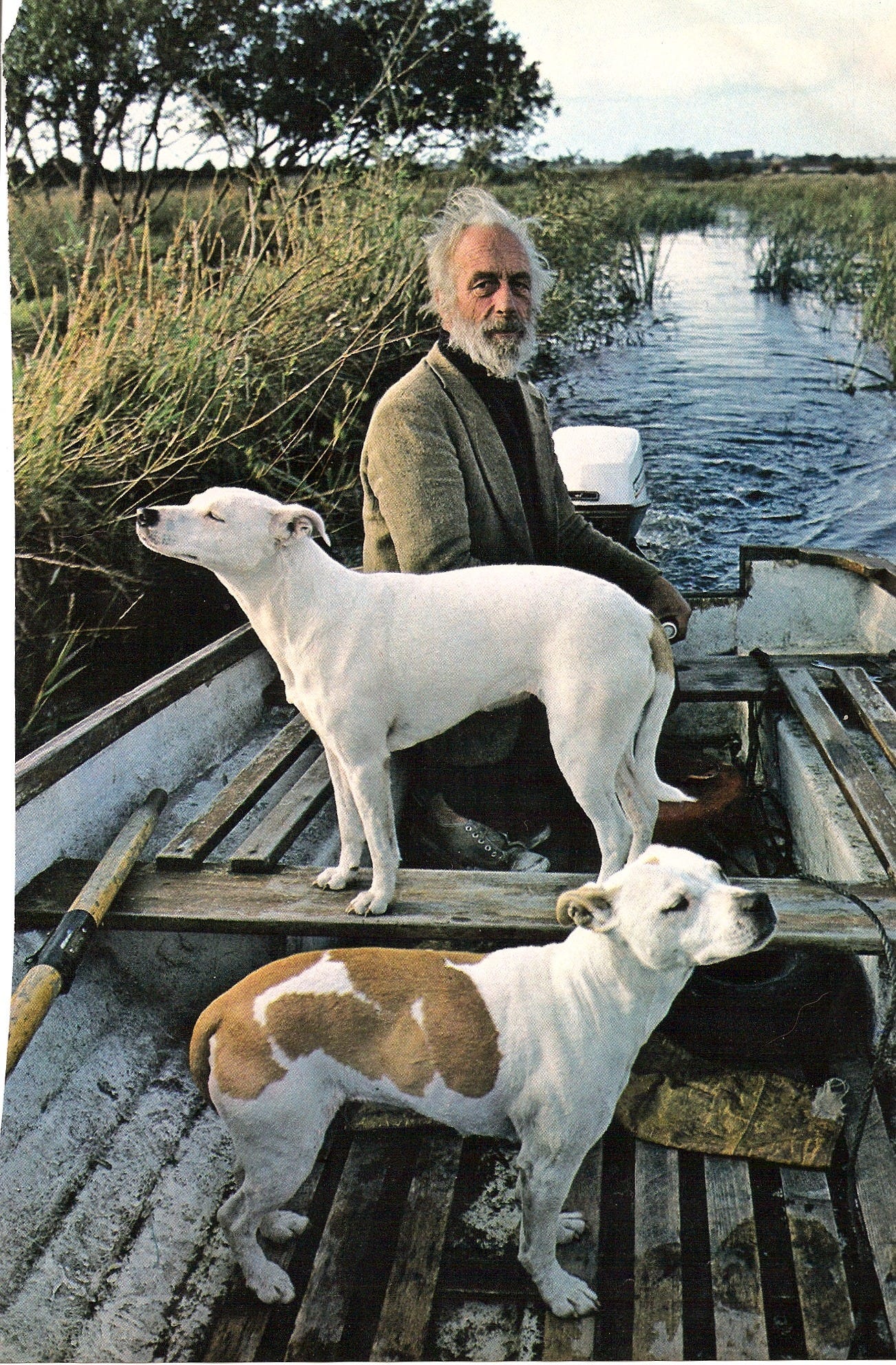

The painting in the film was in fact by Goodfellas co-writer Nicholas Pileggi’s mother, and was an interpretation of a photo from the November 1978 issue of National Geographic.

The man is real. The dogs are real. The photo was part of a 28-page feature titled Where The River Shannon Flows (‘Allan C. Fisher, Jr., and Adam Woolfitt follow Ireland’s longest stream from gentle lakes to wide Atlantic estuary’). Further Googling led me to Brian Leyden, an Irish writer from County Leitrim whose memoir The Home Place begins in 1978 with photographer Adam Woolfitt visiting Arigna to carry out that very assignment. Adam spent quite some time with Brian’s parents, and photographed them on their farm in Crosshill. “Don’t stay too long in this country or it will capture you,” Brian’s father Matt was quoted as saying in the article.

One afternoon at the turn of the century, Brian was a guest on RTE’s TV show Open House. He brought that issue along with him, and the producer recognised the photo of the man and the dogs, telling him there was a painting of it in Goodfellas. This inspired Brian to write The Home Place, as a way of preserving the stories and lives behind those National Geographic photos.

I called Brian, who told me the chap in the photo was called John Weaving. John had retired from a career in banking to become a river nomad, “a water rat” who lived on a 60ft houseboat on the Shannon. John, said Brian, was a navigational consultant and handyman on the river, and something of an eco-crusader, campaigning against the low bridges being built, pushing for proper clearances for family-sized barges. His dogs were called Brocky and Twiggy.

I found more info on John Weaving, including The King Of Lough Ree, a warm article (no longer online) about him by Bernard Loughlin, who was introduced to John while working on the Shannon in April 1974. ‘A tall, skinny, tousle-haired, wispy-white-bearded man emerged from the cabin’s low door and called to Twiggy and Brocky, as the dogs were named, to be quiet,’ he writes of his inaugural encounter. John tells Loughlin how the dogs that morning had killed a nest of rats, ‘breaking their necks one by one with a flick of their muzzles as they tossed the corpses back over their shoulders.’ Smoking Sweet Afton cigarettes, he invites Loughlin for tea on his 60ft barge, the Peter Farrell, which Bernard describes as an alchemist’s den full of tools, maps and books. ‘John Weaving had made a heroic choice,’ writes Loughlin of John’s retirement from banking and his bachelorhood on the Shannon, ‘and was even quite boastful of it, and showed it by how completely he lived as he lived, on the river, all year round.’

Loughlin describes how for 20 years John built harbours, laid buoys and repaired jetties, and in the summers helped tourists if their rented cruisers broke down or crashed. A big character in the community, he once received a letter from Germany addressed simply to Herr John Weaving, The Shannon, Ireland. Brocky and Twiggy, writes Loughlin, would position themselves either side of John ‘like fabulous, hieratic creatures guarding their lord and master from all harm.’ Just as Joe Pesci says: “One dog goes one way and the other dog goes the other way.” I found a photo of John on the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland (IWAI) website, taken in 1963 by naval architect and boat-builder George O’Brien Kennedy. His family were the original owners of the Peter Farrell, and eventually sold her to John after employing him to operate her. The caption for this photo reads: ‘The Kennedy field, just upstream of Jamestown Bridge, in 1963. In picture is the Peter Farrell and John Weaving (standing) in the foreground.’

John Weaving co-edited The Shell Guide To The River Shannon, which was subsequently dedicated to him: on 24 May 1987, before it was completed, he died. He had continued to work on it during his final months in hospital. ‘He became at one with the great river and now has become a permanent part of its legend,’ wrote editor Ruth Delany in her foreword. ‘I know that I speak for his many friends when I say that it was a great privilege to have known him.’

Colin Becker, editor of the Inland Waterways News, tells me John ‘was held in such high esteem in the IWAI that they put up a bronze bust of him beside the harbour in Terryglass a number of years ago’ (photo below courtesy of Sherwood Harrington).

After John’s death the Peter Farrell, says Colin, changed hands a few times and has now been extensively modified and refurbished as a family cruising boat. Here it is in Shannonbridge, October 2011, courtesy of Tina Klug, who tells me the barge today is "much more comfortable" than when it served as John's alchemist's den.

I called photographer Adam Woolfitt to talk about meeting John for that 1978 National Geographic assignment. Adam found the issue while we were talking, reminding himself of the photos as he remembered John. After running into John and arranging to photograph him, Adam told me, they spent a couple of hours together. “We went up and down a little bit on his boat until I found a nice background and made my pictures. I rather liked him, he was a very free spirit, quite independent. He was definitely cut out for nomadic life. He was very pragmatic and very down to earth. He was really a part of the river.” Adam didn’t get to visit the Peter Farrell, instead photographing John on the little rowing boat he used to whizz around on.

Adam hasn’t seen Goodfellas, so was unaware that his photo had been immortalised in paint and exhibited by Martin Scorsese’s mother. I sent him the clip. “Fame at last!” he wrote. “I’ve starred in a Hollywood movie.”

(RIP Adam Woolfitt, who died in November 2023. There is a lovely tribute to him here.)

Of course, having died three years before the release of the film, John Weaving was never to know that he too has been immortalised, in a scene in which Joe Pesci describes his nice head of white hair and Robert De Niro compares him to a dead gangster in their car boot. I’d hope John would have been entertained by his cinematic incarnation, and when I watch Goodfellas in the future and reach that scene I’ll think of him working on the Shannon, smoking his fags, sending Brocky and Twiggy off to kill rats. That painting is no longer just a prop, but a life.

I told Brian I had Adam’s details and was talking to him too; he asked me to remind Adam of his parents. Adam remembers them well. Brian hasn’t seen Adam since his 1978 visit, and asked me to put them in touch so that he can send him a copy of his book, which exists because of him. “When I came to write it I got very intrigued by those photographs and I realised that time had obliterated – more than just John Weaving and his boat and his dogs – it had obliterated nearly everything in the photographs,” Brian said to me. “That whole article, ‘Where The River Shannon Flows’, has had a curious afterlife, quite a life, and that and the book, it means a great deal to me. And now you’re another element to the story.”

I’ve enjoyed learning about John. It’s nice to be a part of his own afterlife.

2021 update:

Martin Scorsese has read this now. After I interviewed him, for The Irishman’s Criterion release, I asked him if I could tell him something. And the conversation went like this:

MS: “What is it, young man?”

AG: “The painting your mother produces at the table in Goodfellas. I heard Nicholas Pileggi’s mother painted it.”

MS: “Yeah, she painted it.”

AG: “But it’s painted from a photograph in a 1970s National Geographic magazine.”

MS: “No, I didn’t know about that. My mother didn’t paint. The only thing that was written in that scene was the painting. Everything else was improvised by my mother and Joe and Bob. That was the only thing that was written, this painting that Nick’s mother did. I didn’t realise it was based on a photograph.”

AG: “A guy who worked on the canals in Ireland. I found out about his life. I’d love to send it to you.”

MS: “That's wonderful. Send it to me. That’s so great, what’s she doing painting a guy in Ireland?!”

I emailed it over, and a couple of days later he sent me a very gracious, hugely touching email about it - about the painting, the scene, and his mother. Needless to say, I was overwhelmed. God bless Goodfellas.

February 2025 update:

A few weeks ago, I was lucky enough to spend an hour talking to Nicholas Pileggi, interviewing him about The Alto Knights. Towards the end of the conversation I spoke to him about this piece and asked him about the painting. Specifically: why had his mother painted it?

“Almost everything my mother painted was from National Geographic,” he explained. “Except when she would come out to… Nora [Nick’s late wife, the great Nora Ephron] and I had a house on Long Island, and my mother painted our barn. She painted pictures of our budgies. After my father died, painting became her passion. She did these slightly primitive things, and wound up doing the two dogs, one dog looking one way, one dog looking the other.”

And how did it end up in Goodfellas? “I mean, we were all working together. And in that scene, Marty’s mother needed something to do and my mother was painting all the time, so I said, ‘Why don’t we give this one to Cate [Scorsese]?’ So I brought the painting in.”

And that was that. The stuff of legend, because of a whim.

“It hangs over my desk in the city,” says Pileggi of the painting’s home now. “It’s actually become a famous painting. It’s amazing!”